How to Get Help Paying for Alzheimer’s Care In These Troubled Economic Times

Moving a loved one into a nursing home is not an easy decision. We want to make sure our loved ones receive the best in medical care and are as comfortable as possible with the transition. There are numerous factors to consider when a family member can no longer live alone because of medical tragedies such as Alzheimer’s, a stroke, a heart attack, or Parkinson’s disease. Not only will we consider the care facility’s services and environment, but the decision will also involve finances: What is affordable? How long will our savings last with all the economic turmoil? Can we consider qualifying them for government benefits?

Is it Necessary to Wipe Out My Family’s Assets to Pay for Nursing Home Expenses?

This guide is provided as a starting point to familiarize you with the topic of planning for long-term care and various government benefits available and their qualification criteria. The following information will explain how Medicaid works. This guide also includes an introduction to the Veteran’s Aid & Attendance Benefits - a benefit many veterans are unaware of that may help offset the costs of medical expenses. Understanding government benefits is critical to anyone who has a family member in a nursing home or is concerned with the cost of long term care. There are legal ways to avoid being impoverished by nursing home costs. In this stressful time, it’s important to make educated decisions. The following information will answer many of the questions that arise when long-term care is needed. These are the same questions which elder law attorneys and health care professionals deal with on a daily basis. If You or Your Loved One Is in Need of Long-term Care, I Recommend You Read This Guide Immediately.

How To Pay For Care

Paying for care can be accomplished in three ways:

-

Private pay - Just like it sounds, this is using your own private funds to pay for the care services needed. This money can come from retirement income sources like pensions and Social Security. It can also come from retirement savings like your IRA and checking or savings accounts, or from stocks, bonds, and mutual funds. Private pay means using your own money to pay the bills.

-

Long term care insurance - This works well if you planned ahead. However, most seniors don’t have long term care insurance, and if the diagnosis is Alzheimer’s it’s too late to apply for this type of coverage because you won’t pass the insurance companies’ underwriting process. Plus, traditional long term care insurance has proven challenging for many seniors because the monthly cost (premium) is experience-rated. Just like your car or homeowners insurance cost (premium) is based on the insurance carrier’s “experience,” so is long term care insurance. This means that if too many people put in claims while you are still paying, then the price you started with is not necessarily the future cost. The insurance company can increase the price by going to the State Insurance Commissioner and showing that they need a rate adjustment; but to you that’s a price increase. A new generation long term care coverage called “asset-based long term care” can be very effective.

- Medicaid - This is a federal- and state-funded program and you must meet strict asset and income guidelines - but it’s not welfare. Medicaid was created along with Medicare to assist aging seniors.

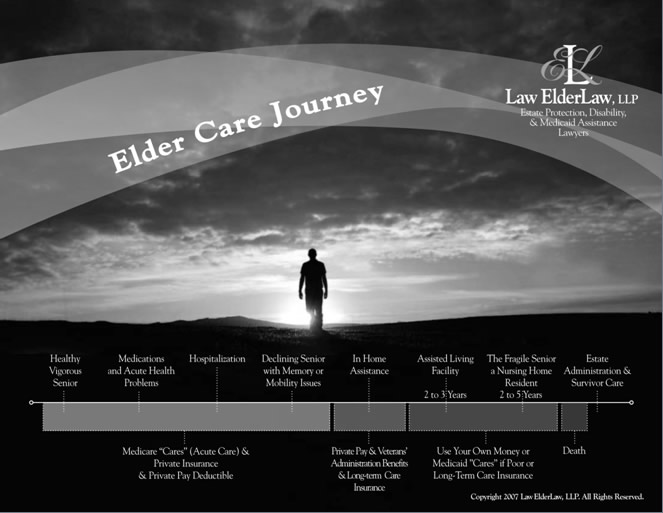

The Elder Care Journey

Copyright 2009 Law ElderLaw, LLP

This visual was created by elder law attorney Rick Law, and it is very valuable in explaining the aging process and what benefits, if any, are available to you at various care levels. This report is focused on Alzheimer’s care, as such, the report is designed with he idea that the diagnosis has already been made and care needs may develop more rapidly than with the normal aging process. However, the visual will help us explain what is available and when it might be available to you or your loved one.

Medicare vs. Medicaid

Medicare and Medicaid sound similar, but are very different and distinct programs. Medicare is a type of public health insurance for those age 65 and older. In essence, it is their primary health insurance coverage. Many seniors are unaware that Medicare does not pay for long term care—it is excluded. The confusion is easy to understand because Medicare does pay for rehabilitation. So, if a senior citizen enrolled in the traditional Medicare plan is hospitalized for a stay of at least three days and then is admitted into a skilled nursing facility Medicare may pay for a while. The maximum number of days one can receive is 100 consecutive days. However, the payment period could be less than 100 days based on the patient’s response to the rehabilitation—improvement is required, otherwise Medicare will determine that the condition is a long term care need and stop funding. Plus, there is a deductible of about $120 per day. This Medicare coverage is really based on the possibility of rehabilitation. Diseases like Alzheimer’s have no known cure today, so rehabilitation is not possible; therefore Medicare will offer no assistance for payment.

Unlike Medicare, few of us have any experience in dealing with Medicaid rules and guidelines. Medicaid is funded by both federal and state funds but is administered on a state level. Therefore, rules can vary from state to state rather dramatically. Medicaid is designed to pay for long term care in a nursing home, and in some instances, for at-home care once you’ve qualified. As previously mentioned, Medicare doesn’t provide coverage for illnesses like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease. So, you would have to either begin the Medicaid application process for this type of illness or else private pay. (Wartime veterans and their spouses have an additional benefit, discussed later).

EVERY reader of this report should understand the differences between Medicare and Medicaid. The chart below is designed to contrast the two programs:

Medicare |

Medicaid |

Health insurance for seniors age 65+ |

Needs-based health care program |

Federally controlled, uniform application across the country |

Controlled state by state, which created different regulations in each state of application |

Pays for no more than 100 days of nursing home care |

Pays for long term care |

Pays for primary hospital care and related medically necessary services |

Pays for medications |

Must have contributed to Medicare system to be eligible and generally be over age 65 |

Must meet income and asset limits to be eligible and be over 65, disabled, or blind |

So, as you can see on the Elder Care Journey visual, benefits must be tied to the stage of care where you or your loved one find yourselves. Medicare is health insurance, and Medicaid is public long term care coverage—but often there are stages in between that require examination and discussion. We will refer back to the Elder Care Journey throughout this report.

So Many Myths About Medicaid

Isn’t is true that you can give $10,000 to each of your children “without penalty”? Can’t you just put your kids’ name on your accounts and solve these problems? Or perhaps you’ve heard there is an annuity that allows you to “flip the switch” and it will solve these long term care problems. Sometimes, retirees get so frustrated they tell me they are going to give it all to their kids—that’ll solve it, right?

In each of the cases above the answer is the advice given is wrong! The $10,000 is now $13,000, and that is an IRS rule that has nothing to do with Medicaid eligibility—two different rulebooks. Putting your children’s names on your accounts protects none of the money, because each state has a “source of funds” rule, and if your kids didn’t put the money into the account, they get no rights of ownership of the funds. The state basically erases them from the account unless your family can prove otherwise. Annuities can play a role, but the laws have changed and it’s not like it used to be—there is no magic switch to flip—it’s a complex process today. As for “giving it all to the kids,” that opens up the possibility of their problems bumping into your money. My golden rule has always been, don’t give to your son or daughter directly what you wouldn’t give to your son-in-law or daughter-in-law. Plus, most retirees don’t realize the tax implication of these gifts. For instance, transferring a house to a child changes the property tax classification from owner-occupied to non-owner-occupied—so your property taxes will go up. Accountants have a fancy term called “cost basis.” Cost basis is what you paid for an asset. So, if Mom and Dad paid $40,000 for their house 60 years ago and today it’s worth $240,000 and the house is transferred to the kids once Mom and Dad die, the kids pay tax based on a $200,000 capital gain! Done properly, the kids would have received a step up in basis resulting in no tax.

To Qualify For Medicaid You Have To Spend Down

Each state has a different set of rules, but generally a single or widowed person can keep only $2,000 in total assets and still qualify for Medicaid and the rest must be “spent down.” Again, this varies—for example, in Ohio, it’s $1,500 and in Missouri it’s $999—but normally it’s about $2,000. The spend down process includes nearly all assets. The exempt assets are:

- Home (equity up to $500,000) if “intent to return” is established

- Personal belongings and household goods

- One car or truck

- Burial spaces and certain related items for applicant and spouse

- Irrevocable pre-paid funeral contract

- Up to $1,500 of face value life insurance or less; if the face value exceeds $1,500 the cash value is countable as a resource for payment

All other assets are generally non-exempt and are countable as resources available for payment. Basically, any item of value that can be turned into cash is a countable asset unless it is listed above as exempt. Non-exempt items would include:

- Cash, savings and checking accounts

- Credit union share and draft accounts

- Certificates of deposit

- US Savings Bonds

- IRAs, 401(k)s, Keogh plans, 403(b) and all other defined compensation plans

- Pre-paid funeral contracts that can be cancelled

- Trusts (depending on the terms and conditions of the trust)

- Real estate (other than primary residence)

- More than one car

- Boat or recreational vehicles

- Stocks, bonds and mutual funds

- Land contracts or mortgages held on real estate sold

Single Applicants

Single applicants can become eligible for Medicaid by spending down to meet the eligibility requirements.

This doesn’t mean a single person cannot protect his or her money. There are strategies designed to help your loved one not run out of money and out of options. Gifting intra-family is much more difficult when faced with disability and the real possibility of a future long term care need. This is especially true since a new law, called the Deficit Reduction Act, lengthened the look-back period from 36 months to 60 months. The “look-back period” is the period of time the state is allowed to examine your finances. Penalty periods from Medicaid eligibility are based on the activities that took place during that 60-month period the state puts under review. You may be thinking, “There is no way the state is going to do that!” Let me be very frank and clear–I guarantee that they will.

I often think if I just had a crystal ball and knew how long a person was going to live or how much time would pass before they would need skilled care, I could turn all of this planning into a math equation—a science—but long term care planning is more art than science.

For a single person, you need to focus on income first. How much does he/she make in Social Security? Does he/she receive pension income? Is he/she eligible for a veteran’s benefit? Then consider the asset base. For example, let’s say George, a widowed veteran, had Social Security income of $1,300 and a company pension of $1,100. His physical health was exceptional, but his dementia became a huge concern for his family. Based on his need for 24-hour-a-day care, the family found a facility they trusted and allowed the facility to care for Dad. The monthly cost would be $6,200 per month; his pharmacy bill averages $300 per month. Dad had saved his whole life and had amassed $400,000 in mostly bank-held assets; how can he pay for long term care?

In this simple example, George’s total income is $1,300 + $1,100 = $2,400 per month. He is also eligible for a wartime veteran’s pension called the Aid and Attendance benefit (more on that eligibility process to come), and his benefit amount would be $1,644 tax free dollars per month—so George’s income with benefits would be $4,044. His care cost and medications cost $6,500 per month. George has a $2,456 per month shortfall. Of course, prices will go up and his shortfall may grow, even with cost of living increases to his Social Security. If we take the shortfall times 60 months we can calculate he would need at least $147,360 of his $400,000 to pay through the Medicaid look-back period. Now that won’t be enough, and the family should set more aside for his care, but it’s a start… But again this is not an appropriate math equation—costs will change and there are too many variables to predict an exact amount to gift and an exact amount to leave “at risk.”

Married Couples

Married couples seeking care with Medicaid funds face unique problems because there are so many logical reasons these rules shouldn’t apply to you—like, “I’m fine. My wife’s name isn’t on the majority of our savings and investments anyway.” Think again – you’re wrong! The state views the marital assets as a unit and is blind to whose name is on the account—it all counts towards the spend down. Some States like Florida do grant an exception for the healthy spouse’s IRA account, but for the majority of you reading this report, everything counts.

Then, someone will always say, “Just give it to your kids and it will be fine.” This is actually a major rule violation for Medicaid called an “improper transfer.” There are very strict gifting rules for Medicaid eligibility and it must be done correctly. You must be careful, because the waters here get treacherous quickly, and mistakes often are not forgiven and are sometimes impossible to fix.

Planning For A Disabled Spouse

What happens if it is your spouse who needs care? You not only have to consider the care costs but you will also need income and assets to live on. The law that defines these rules is called the Spousal Impoverishment provision of the Medicare Catastrophic Act of 1988. This is the rule that tells us how assets must be divided.

Basically, the couple “gathers” all their countable assets and divides them in half. The spouse at home is called the “community spouse” and the one in care the “institutionalized spouse.” The maximum in any state that a community spouse can keep is $109,560. A few states allow the community spouse to keep the maximum of (up to) $109,560. However, the vast majority of states divide the assets in two. The institutionalized spouse can keep $2,000. The amount the community spouse is permitted to keep is called the Community Spousal Resource Allowance (CSRA). Each state also permits the community spouse to keep a minimum amount of income this is called the Minimum Monthly Maintenance Needs Allowance (MMMNA) and it is set by federal guidelines; currently (2009) it is $1,750 per month. So, if a female community spouse has $500 in Social Security income and her disabled husband who is eligible for Medicaid has Social Security of $1,250 then all of his income would be diverted to his Community Spouse to get her income to the MMMNA of $1,750. However, if she, the community spouse, earned $2,000 a month between her Social Security and pension, his full $1,250 would go to the nursing home as a co-pay. This is a general rule, but planning alternatives exist. Consider the following case study.

Sam and Patty’s story:

Sam and Patty dated through high school got married and lived their entire lives in a small town in rural Kansas. Three days after their 52nd wedding anniversary, Patty, who has Alzheimer’s disease, wandered from their home. Sam was relieved when Patty was found hours later, wet and cold, sitting on a street curb, incoherent. It was the wake-up call for Sam that at his age he just couldn’t provide the care Patty needed. She was dehydrated and hospitalized for two days. Her doctor told Sam she was probably only a few hours away from dying out in that weather. Sam felt quite guilty because he often needs an afternoon nap. Patty frequently wanders through the house during the night, keeping him up and not well rested for the caregiving tasks he performs each day. Sam, a self-proclaimed “Depression kid,” wanted to care for his wife the best way he could—but he was floored by the cost of skilled care. Now faced with the reality that skilled care was where his wife needed to be for her own safety, Sam digested the reality that at $6,000 per month, their entire life savings would be gone in less than two years!

Sam and Patty had the following assets:

Savings account $37,000

CDs $50,000

Money market $10,000

Checking $ 5,000

House (no mortgage) $80,000

Total countable assets were about $100,000 (home excluded).

Sam was worried. His neighbor told him not only would they take all the assets, he would even have to give them their Social Security checks. “How will I live?” Sam wondered.

There is good news for Sam. It’s possible for him to keep his income and most of their assets and still have the state Medicaid program pay for Patty’s care. He learned from an advisor who specialized in long term care planning that he could take the $50,000 viewed by the state as his wife’s money (as the institutionalized spouse) and turn it into an income stream for him that increased his income and still meet the eligibility requirements for the Medicaid spend down nearly immediately. The planning was completed with the help of a qualified elder law attorney and Patty received the care she deserved—and Sam accepted his role as Patty’s care advocate, visiting her every day and making sure she was well fed, clean, and safe.

Why Can’t I Just Give Away $13,000 Per Year to Each of My Children?

This can be confusing, because most people have heard that the federal gift tax regulations allow them to give away $13,000 per year (2009 figure) without any gift tax. (Previously it was $12,000 and before that it was $10,000 per year). This is a federal tax exemption that has nothing to do with Medicaid, which has its own set of rules. Even small gifts can be aggregated to establish a large period of ineligibility. This means all your $500 gifts to the grandchildren and your $1,000 donation to the local church add up against you for Medicaid eligibility. If over the past 60 months you gave away $8,500, then you will be penalized for months based just on those gifts and that is before the state examines your assets. Still, some parents and grandparents want to make gifts tot heir family. In this situation, consider the following:

Tony, Mim and Steven: Their Story

Steven came in with his mother, Mim, to see what could be done to help his parents. His father, Tony, was a healthy man of 73 years when he had a stroke—“It’s like he is gone now; he was such a strong man, and now he can’t even open his eyes.” Steven said, “Mom is terrified that she is going to lose her house!” Mom added, “Can’t I just give everything to Steven?”

Steven had heard about Medicaid benefits but didn’t want his mother left destitute. He would happily hold onto Mom’s money for her. You could see the care and love in his eyes—he just wanted to help his mom and make sure his dad was well cared for—this was obviously not about him.

But a gift, in Medicaid’s view, is a transfer—and there are very specific rules about transfers. Gifts made after the enactment of the February 8, 2006 Deficit Reduction Act are subject to a “five year look back period.” This means that if the gifts were made any time in the previous 60 months, the state would not recognize the gift and would expect the family to give the money back to pay for care. Mim felt things weren’t looking good for them, and I had to honestly say that the new rules are very “nit-picky”—but set up properly, a good portion of Mim and Tony’s estate could be protected and still qualify Tony for Medicaid. Again, this has to be done just right, and a knowledgeable advisor can guide you through this process.

Eligibility Is Only The First Step

Shock is the normal response when you learn that your home, which you willed to your children, will be sought after by the government through a process called “estate recovery” after your death. Estate recovery is the process in which, after you die, the state comes back and collects on any money it paid out on your behalf for your care. The asset recovered most often is the family home, because the Deficit Reduction Act initially exempts up to $500,000 of home equity during your lifetime. Many states have an “intent to return” rule so the house is off limits during life—but post-death, the state wants to recover what it paid out. This little-debated law affects hundreds of thousands of families where a spouse or an elderly parent needed nursing home care. Federal law requires each state to attempt to recover the benefits paid out from the recipient’s probate and, in some cases, non-probate estate.

This is a huge part of the planning process considering that two-thirds of the nation’s nursing home residents have their cost of care paid for by Medicaid. This “trap” is the result of the applicant being permitted to keep their home as an exempt asset. However, at death there is not an exemption any more, and the home is subject to the recovery process. Since, Medicaid rules have changed a number of times, you need a knowledgeable advisor to guide you through these tricky rules.

My Dad Served In WWII—Does That Matter?

It sure does. The Veteran’s Aid & Attendance Benefit has often been referred to as “the VA’s best kept secret.” When you look at the Elder Care Journey chart, Medicaid does the heavy lifting at the skilled nursing home level, and some benefits may be available for at home services through waiver programs, but availability in these turbulent economic times is limited. However, the VA benefit is available to you, if you qualify.

This non-service connected pension benefit is there to help wartime veterans with unreimbursed medical expenses. Even the spouse of a wartime veteran is eligible. Eligibility has requirements, but you don’t have to be impoverished to qualify. Disability for this benefit is defined by either being over the age of 65, permanently disabled and unable to work, or homebound and in need of regular aid and attendance—and it can be at home, in assisted/supportive living, or in a nursing home. Again, the program is based on actual financial need, so there are income and asset limitations.

The program allows for the following benefit amounts (2009 figures):

Married wartime veteran Up to $1,949 per month tax-free

Single wartime veteran Up to $1,644 per month tax-free

Widowed spouse of a wartime veteran Up to $1,056 per month tax-free

Successfully applying for this benefit relies on understanding how the VA views income. It would seem logical that our income is what we bring in each month. However, the truly critical calculation is determining Income for VA Purposes (IVAP). The income the VA is interested in is determined by taking gross income minus unreimbursed medical expenses (UMEs).

IVAP = Gross Income – Unreimbursed Medical Expense

Unreimbursed medical expense include doctor’s fees, dentist’s fees, Medicare premiums and co-payments, health insurance premiums, transportation costs to physician’s offices, and the care costs of assisted living facilities or in-home aides.

Consider Chester Soblek

Chester is a 65-year-old Korean wartime veteran who needs in-home assistance daily. His income is $1,700 per month from Social Security and a small pension. The in-home care cost paid to the agency providing the care is $3,000 per month, and he has out-of-pocket prescription costs of $200 per month. Chester is very concerned because he has $40,000 in savings and at a rate of $1,500 per month from his savings, he will be out of money in a less than two years, because he still has other bills other than his care, like groceries and utilities—and this assumes that care costs stay the same, which he knows they won’t! Chester’s health needs requires he get help, but absent his financial resources Chester will have to go to a nursing home—and he absolutely wants to stay in his home and frankly doesn’t need full skilled care at this time. This is why planning with a knowledgeable advisor is so critical. Financial missteps or lack of knowledge about what’s available can lead to care arrangements that are not suitable for one’s care needs. So, let’s look at the math:

Chester’s Income: $1,700

(minus) his Unreimbursed Medical Expenses: $3,200

= A Negative IVAP of ($1,500)

For Chester’s case we will assume that $40,000 in assets is acceptable (remember you don’t have to be impoverished) and his income for VA purposes is a negative $1,500, so he is eligible for the full veteran’s benefit of $1,644 per month tax-free. As a result, Chester has adequate income, because of this benefit, to pay for his care needs at home just the way he wanted.

You’ll Need Help Getting This Benefit

It’s important to know there are only three types of authorized professionals who can assist you in filing a claim for this Veteran’s benefit:

- An attorney licensed to practice law in your state who is also accredited with the VA

- A Veterans Service Organization (VSO) such as your local VFW or American Legion

- A state or county official of the Department of Veterans Affairs in your state.

Be careful of anyone offering you assistance for a fee. You need qualified professional assistance and planning because new VA rules can create complications and legal situations. But it is unlawful to charge a fee for filing a VA application.

Be Aware Of The “Medicaid Bear Trap”

For VA planning purposes, gifts carry very short periods of ineligibility; whereas, Medicaid views gifts entirely differently. In other words, what works for VA may cause severe and long periods of ineligibility for Medicaid. Gifting today is a very technical strategy that requires professional guidance. Done improperly, it can create huge gaps in care. These gaps are created by improper transfers where the state Medicaid Department will NOT pay for your care, and your family is unable to “pay back” the gift, and the care facility can’t afford to provide the care without payment. This is a horrible position to be in, and proper planning with a knowledgeable advisor will protect your health care well-being.

Eligibility For The VA Aid & Attendance Benefit

You must have served during a time of war. The official dates for periods of war are:

Mexican Border: May 9, 1916 to April 5, 1917

World War I: April 6, 1917 to November 11, 1918

April 1, 1920 if served in Russia

World War II: December 7, 1941 to December 31, 1946

Korean War: June 27, 1950 to January 31, 1955

Vietnam War: August 5, 1964 to May 7, 1975

February 28, 1961- if served in Republic of Vietnam only

Persian Gulf War: August 2, 1990 to [date not yet determined]

Other Groups Who Qualify

If you belong to any of these groups and received a discharge by the Secretary of Defense, your service meets the active duty service requirement for benefits:

- Recipients of the Medal of Honor

- Women Air Force Service Pilots (WASPs)

- WWI Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators Unit

- WWI Engineer Field Clerks

- Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC)

- Female clerical employees of the Quartermaster Corps serving with the American Expeditionary Forces in WWI

- Civilian employees of Pacific naval air bases who actively participated in defense of Wake Island during WWII

- Reconstruction aides and dietitians of WWI

- Male civilian ferry pilots

- Wake Island defenders from Guam

- Civilian personnel assigned to OSS secret intelligence

- Guam Combat Patrol

- Quartermaster Corps members of the Keswick crew on Corregidor during WWII

- U.S. civilians who participated in the defense of Bataan

- U.S. merchant seamen who served on block ships in support of Operation Mulberry in the WWII invasion of Normandy

- American merchant marines in oceangoing service during WWII

- Civilian Navy IFF radar technicians who served in combat areas of the Pacific during WWI

- U.S. civilians of the American Field Service who served overseas under U.S. armies and U.S. army groups in WWII

- U.S. civilian employees of American Airlines who served overseas in contract with the Air Transport Command between 12/14/41 and 8/14/45

- Civilian crewmen of certain U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey vessels between 12/7/41 and 8/15/45

- Members of the American Volunteer Group (Flying Tigers) who served between 12/7/41 and 8/14/45

- U.S. civilian flight crew and aviation ground support of TWA who served overseas between 12/14/41 and 8/14/45

- U.S. civilian flight crew and aviation ground support of Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corp. who served overseas between 12/14/41 and 8/14/45

- Honorably discharged members of the American Volunteer Guard, Eritrea Service Command, between 6/21/42 and 3/31/43

- U.S. civilian flight crew and aviation ground support of Northwest Airlines who served overseas between 12/14/41 and 8/14/45

- U.S. civilian female employees of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps who served in the defense of Bataan and Corregidor from 1/2/42 to 2/3/45

- U.S. civilian flight crew and aviation ground support of Braniff Airways who served overseas in the North Atlantic between 2/26/42 to 8/14/45

- Chamorro and Carolina former native police who received military training in the Donnal area of central Saipan and were placed under command of Lt. Casino of the 6th Provisional Military Police Battalion to accompany U.S. Marines on active, combat patrol from 8/19/45 to 9/2/45

- The operational Analysis Group of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Office of Emergency Management, which served overseas with the U.S. Army Air Corps from 12/7/41 through 8/15/45

- Honorably discharged members of the Alaska Territorial Guard during WWII

More Details…

Who is eligible for the non-service-connected pension?

- Honorably discharged veterans, surviving spouses, or children of any military, naval, or air service. Also includes certain other special groups such as:

- Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC)

- Merchant Marines from WWII

- U.S. civilians of the American Field Service

- Plus 30 more! See list later in this guide.

- Served in active duty 90 consecutive days, one of which was during a period of war

- At least 65 years old or Permanently and Totally Disabled

“Permanently and Totally Disabled” is defined as:

- Receiving long-term nursing home care; or

- Receiving Social Security disability benefits; or

- Unemployable as a result of disability reasonably certain to continue throughout the life of the person.

The veteran’s current disability does not need to have any connection to the veteran’s actual time in the armed forces. (Non-service-connected disability can be Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, etc.)

Other requirements:

This is a needs-based program with income and asset tests.

- Income limitation

- Gross income MINUS certain expenses

- Unreimbursed medical expenses of veteran and his/her household

- Certain educational expenses

- After reducing gross income by the above expenses, net income must be lower than $11,181 to $22,113, depending on your circumstances

- Net worth limitation

- In addition to your house, car, life insurance, burial policies, and annuities in payout status, the maximum amount you can generally have is between $50,000 and $80,000 in assets, including CDs, stocks, bonds, etc. This is just an estimate and figures for the net worth criteria are significantly lower and are based on various factors.

If your net worth is higher, consult with a qualified attorney for an appropriate tax analysis to see if transferring some of your assets may qualify you.

The Benefits Available

(2009 figures)

Table 1:

Special Monthly Pension Rates

Paid to veterans age 65 or older OR

Permanently and Totally Disabled

Situation |

Maximum Annual Pension Rate |

Maximum Monthly Check |

Permanently and totally disabled veteran |

$11,830 |

$985 |

With one dependent |

$15,493 |

$1,291 |

Permanently and totally disabled and also housebound |

$14,457 |

$1,204 |

With one dependent |

$18,120 |

$1,510 |

Permanently and totally disabled and in need of regular aid and attendance |

$19,736 |

$1,644 |

With one dependent |

$23,396 |

$1,949 |

Increase for each additional dependent child |

$2,020 |

$168 additional |

Table 2:

Death Pension Rates

Paid to Veteran’s Surviving Spouse

Situation |

Maximum Annual Pension Rate |

Maximum Monthly Check |

Surviving spouse |

$7,933 |

$661 |

With one dependent child |

$10,385 |

$865 |

Surviving spouse is permanently housebound |

$9,696 |

$808 |

With one dependent child |

$12,144 |

$1,012 |

Surviving spouse is in need of “regular aid and attendance” |

$12,681 |

$1,056 |

With one dependent child |

$15,128 |

$1,260 |

For each additional dependent child |

$2,020 |

$168 additional |

Getting Your Ducks In A Row

All of this seem quite confusing. The Elder Care Journey is designed to identify the most likely payment assistance for you as care needs progress. Your best financial defense is to plan early and to get your applications for possible benefits into the system as quickly as possible. During economic downturns we all face the real possibility of funding cuts. As our country continues to “bail out” in billions, your loved one faces a costly journey. So, the sooner you move forward and start the planning process, the better.

If you need help, a great place to start is at www.alzheimershope.org – there you will find the names and contact information for lawyers and financial advisors who specialize in asset protection and long term care planning. Again, to ensure your loved one gets the best care, you should aggressively pursue finding competent professional guidance to identify all the potential public benefits available to help finance the care costs.

Alzheimer's Hope Forum & Message Boards

Alzheimer's Hope Forum & Message Boards